“Real change occurs from the bottom up; it occurs person to person, and almost always occurs in small groups and locales, then bubbles up to larger vectors of change.” – Paul Hawken

The dynamics of the built environment are in constant flux – subject to the whims of emerging technologies, public health crises, and climate change. In 2020, more people than ever have begun to feel the squeeze of these issues, and the discussion around resiliency has become reactive to events directly affecting our daily lives. COVID-19 has grounded businesses, schools, and strained our healthcare system beyond the brink. Wildfires ravaged entire continents for months at a time. In response, we’re seeing a concerted effort at the design table that addresses these issues in the built environment. The tools are now coming online to demonstrate and integrate the resiliency measures necessary to create a sustainable future, but the onus remains on the A/E/C community to advance these measures as a matter of standard practice.

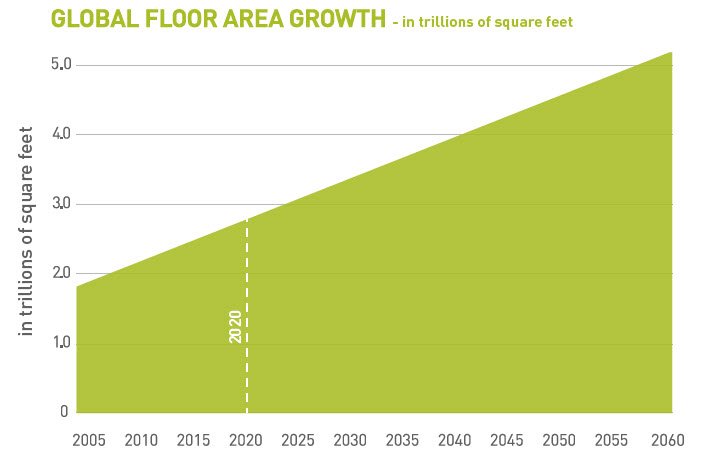

It’s a well-known fact – buildings generate 40% of the planet’s annual greenhouse gas emissions. What’s more, according to Architecture 2030, the global rate of new buildings constructed is expected to grow the size of an entire New York City, every month, for the next 40 years. In order to even come within hailing distance of our decarbonization goals, these buildings must operate at net-zero carbon. And to do that, we need to think about carbon more holistically. This means minimizing energy use, utilizing all-electric systems to avoid combustion emissions that come with burning gas on-site, and tying in renewable generated power. But beyond emissions, we need to consider the carbon impact of materials that go into these buildings and select lower carbon alternatives where possible.

What follows are trends we see across the design industry that have real potential to deliver a low carbon future.

The Convergence of Advocacy and Sustainable Design

It’s been two years since the landmark Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) dropped like a ton of bricks its Special Report on the impact of Climate Change. And while the A/E/C industry isn’t the only one racing to meet the incredibly ambitious benchmarks necessary to avoid the worst consequences of climate change, 2020 is the year we need to move past merely recognizing the incredible impact our work has on global emissions and take more direct action in our communities.

Global climate marches and youth activism have amplified the urgent need for governments and businesses to address climate change strategically and meaningfully. The resulting momentum is changing public opinion and has given the sustainable design industry a leadership position in this effort, as building developers and owners are increasingly requesting expertise for how their projects can satisfy climate goals. At the same time, building design experts can capitalize on this momentum now by increasing our involvement in policymaking locally and regionally to accelerate sustainable development in our communities – while creating an exciting pipeline of work!

At Glumac, our Sustainability and Energy teams are working actively with policymakers and advocacy groups to create the conditions that will facilitate major change. We’re working to develop a Living Building Pilot program in Portland, similar to the program already launched in Seattle, which incentivizes renewable and regenerative building design. And In Seattle, our energy group is working with the State of Washington to push what’s already considered one of the strictest building design codes in the country to enforce greater levels of sustainability and resiliency in new and existing buildings. And our Los Angeles energy group is working with the California Energy Commission and its state-approved software development team on revisions and enforcement measures to California’s energy code. They are also working with the state’s investor-owned utilities (PG&E, SoCal Edison, etc.) and Department of Energy on creating test procedures and efficiency standards on various HVAC equipment.

In the materials world, our architectural partners are leading the charge. One area of designer-led advocacy is manufacturers producing more Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs), largely in response to requests for greater transparency into the carbon impact of building products. EPDs – a statement that provides a clear snapshot of the environmental cost associated with a given product – are a crucial tool that help us make more informed design decisions and lead to more low-carbon outcomes. But they’re still not universally available, so it falls on designers to continue demanding them, not just for transparency’s sake, but also to create a market of better products. BuildingGreen’s letter calling for more sustainable products from mechanical, electrical, and plumbing manufacturers is a good example of how to do this. It’s providing firms a method of engaging directly with manufacturers and providing them with the specific product gaps designers need filled before they can take the necessary leaps forward in low carbon design.

The incredible minds within our industry hold the answers to these major problems we face. But it’s only through this kind of direct advocacy that any kind of meaningful change will happen. The path to mitigating climate change is a hard one to cut, but the meaningful steps are beginning now.

Embodied Carbon is the New High-Performance Frontier

Performance has always been associated with a building’s energy usage and water usage – and is generally measured by how well it conserves resources. But climate change has altered that definition. A building’s carbon emissions are now the most vital metric in determining its performance. And the most effective path to achieving this new level of high-performance building design is through lowering its embodied carbon.

The tools to accomplish this are now coming online, thanks in large part to building industry experts forging ahead on their own and creating ways to identify building materials that offer significant embodied carbon reductions.

“The level of product evaluation now available to designers, manufacturers, and policymakers is making a low carbon future possible.”

One such example is the Embodied Carbon in Construction Calculator (EC3). The tool, developed by Skanska and several partners, calculates carbon emissions embodied within a range of building materials, and provides clarity in the connection between design and procurement’s role in lowering embodied carbon. Another example is BuildingGreen’s recently released top 10 innovative green building products for 2020. It’s an invaluable list: from products to replace blown insulation, to medium-density fiberboard panels made out of rice straw, to gypsum that uses 25 percent less water, its most touted materials present not just energy and carbon savings while in use, but also carbon savings from lighter production and manufacturing processes.

The level of product evaluation now available to designers, manufacturers, and policymakers is making a low carbon future possible. The next step is incorporating these tools into how we talk about building performance with real estate developers and owners, so they can better understand how their decisions impact the project’s triple bottom line.

The Urban Land Institute has created a document for real estate professionals to better understand and advocate for low-carbon materials, and the American Institute of Architects (AIA) – through its commitment to the 2030 Challenge – has begun promoting the Design Data Exchange (DDx), for designer-based metrics on carbon. Finally, the Sweden Green Building Council has launched NollCO2, which sets clear goals for reducing embodied carbon and construction carbon.

In our LEED material consulting work at Glumac, we have seen that it takes a pro-active approach to get lower carbon materials incorporated into a design, and then purchased and actually installed. But when we get it right, the project has an easier LEED documentation experience and can point to real improvements in the carbon performance and environmental impact of a new building. There’s even a new LEED v4.1 pilot credit for projects that demonstrate an embodied carbon reduction, without requiring a full Life Cycle Assessment. We are advocating for increased adoption of these tools (and others, such as the Arc platform that USGBC is using to track a project’s process to LEED Zero throughout this year and beyond. And judging from our conversations at February’s USGBC Town Halls on LEED Zero, we anticipate the industry at large will do the same.

Quantifying “Healthy Building Design”

Glumac has long-standing partnerships with the International Living Future Institute and biophilic design advocates like Terrapin Bright Green. Our sustainability team has worked with these organizations to educate the industry on approaches to creating spaces that perform efficiently and promote wellness for occupants. We’ve illuminated the human case: humans now spend more than 90% of our lives indoors, and it stands to reason those spaces should be promoting healthy outcomes. But there are still a lot of questions over how to quantify the business case, but to also quantify what a healthy building truly is.

The technology to monitor and generate data is well beyond where it was 10 years ago, but we’re still trying to nail what the most effective actions are. The Arc platform is free and empowers us to gather uniform data on more projects than ever. And we can meter everything from CO2 to VOCs to levels of particulates in the air. But we’ve yet to develop a baseline of effective action to take with that data to improve the health of our buildings.

For more details on our scope of healthy building design experience, head over to our project portfolio at glumac.com

We are becoming increasingly aware of how the materials we choose impact the health of occupants. Flame retardants in fabrics is one area. San Francisco has already restricted the use of flame retardant chemicals in furniture construction in response to the negative health impacts such chemicals have on the people who manufacture and use them. But while we’re getting better at identifying what’s bad, the design industry’s ability to act on it remains in many ways a Catch-22. Improved products come on line, and Red Listed materials are becoming much more understood, but owners often feel they remain too expensive. But, the growing industry for these products is proving otherwise. The options are numerous, as seen on various materials databases such as UL Spot, Mindful Materials, and Transparency Catalog, and price is on par with conventional comparables.

Bringing Equity to the Forefront of Conversations

Social equity is a very local conversation that requires local knowledge and local partnerships, often with housing authorities, community groups, business associations, governments, and nonprofits. And there remains so much work to be done on all levels. We need better representation on design teams (e.g. in the a/e industry, the population of full-time workers who identify as women still remains under 20 percent), so our project decisions reflect the needs of diverse peoples. And as standard practice for any project, we need to reach out to these local partners to understand the diversity of communities in a place, issues of accessibility, and needs for services and amenities for public facing portions of the design. Often a more creative and dynamic design solution emerges from a challenge when it reflects the needs of people inside the building and the broader community who will interact on a variety of levels with the building on a daily basis.

“Equity is more than a topic of who benefits from design. It’s equally about how building emissions and storm and sewer conveyance will impact human health and quality of life in surrounding areas. “

But equity is more than a topic of who benefits from design. It’s equally about how building emissions and storm and sewer conveyance will impact human health and quality of life in surrounding areas. The environmental community is often faulted for neglecting the intersectionality between environmental issues and communities of social and economic diversity. Last year at Greenbuild, Enterprise Green Communities led a session alongside the International WELL Building Institute, titled “Using Health Data to Inform Design Strategies.” The organization spoke of the its efforts to integrate health into affordable housing projects, in part through its Health Action Plan with the USGBC. This is a positive step, with access to healthy and affordable housing still being a crucial need in essentially every city around the globe. But the understanding of how design choices impact our communities at large needs to remain at the forefront of the equity conversation.

This intersectionality is improving. “Environmental justice” is an increasingly useful way to tie together our environmental and equity goals. In Portland, a community-led ballot initiative led to the creation of the Portland Clean Energy Fund – a pool of funding that supports a lower-carbon future for citizens who are not usually part of development discussions. We’re also working with the Energy Trust of Oregon to study the cost-drivers associated with net-zero multifamily construction, and to develop resources design teams and energy modelers can use to estimate costs early in design, making it easier to optimize energy savings. Nationally, the NAACP’s initiative on Centering Equity in the Sustainable Building Sector will be a leader in making our equity goals a reality.

This type of hand-in-glove engagement with governmental and advocacy groups must continue to grow throughout the coming year.

Mass Timber is on the Rise – But Conservation Remains a Concern

Mass timber is gaining more acceptance as a more a renewable material and biophilic design choice. But it’s perhaps most notable as a building material with a very low level of embodied carbon. We’ve been working on a number of mass timber projects here at Glumac, most notably the First Tech Credit Union Headquarters in Hillsboro, Oregon. It presents a unique design challenge from an MEP perspective, but the results are as beautiful as they are sustainable.

Whether for established products like Glulam beams or newer products like Cross Laminated Timber or Nail Laminated Timber, we are seeing more interest in wood construction for larger projects – this net-zero carbon neighborhood is a particularly exciting example. At the same time, communities have come to expect forests to provide a broad spectrum of benefits—economic returns, carbon storage, protecting water, a habitat for animals, etc. As more projects demand mass timber solutions in 2020 and beyond, we need to keep sourcing in mind to avoid unintended consequences of a new mass timber boom. One of the biggest challenges is finding ways to reward forest owners for their better management practices. Premiums for Forest Stewardship Council (FSC)-certified forest products often go to distributors or mills – while FSC landowners sell logs at market rate to end up in unlabeled products, and there are still very few options for certified mass timber.

This rise in demand means we all need to learn more about the “woodsheds” that feed into our building projects. Understanding where and how our products are sourced, whether certified or not, will help us deliver on the promise of this low-carbon building material, and while supporting ecosystems and rural communities.

Expanding Opportunities in Resilient Design

In recent years, the building design community has seen the conversation around “green building design” shift from “sustainable” to “resilient.” Sustainability was about finding balance between use and conservation. More and more, resiliency has become a response to climate-related scarcity and crisis (e.g., drying watersheds, wildfires, public health crisis, and flooding). It should still be seen as an opportunity to design built environments that operate more sustainably during normal conditions. Age-old passive design strategies like daylight harvesting and natural ventilation reduce energy demand, but can also keep buildings habitable during a prolonged outage. Or, divorcing buildings from local infrastructure by, for example, designing a building to store and treat solid waste onsite can allow it to operate if municipal systems no longer function. Adding these features to existing buildings can have a long payback period, but bundling these strategies as resiliency upgrades can improve the financial case for deep retrofit, as they pale in comparison to the potential cost of a damaged building or closed business.

“Our ability to model and synthesize data that projects future impacts and to demonstrate system effectiveness is well beyond where it was a decade ago.”

There is no one baseline solution, however. So the key to resilient design is being hyper local. Building professionals must break out of their business-as-usual designs that merely meet state and local code and instead embrace ones that address the risk of their local conditions given climate change and risks to public health. These conversations need to intensify at the design table throughout 2020 to make sure projects begin meeting the audacious goals ahead of us to avoid climate catastrophe. However, our ability to model and synthesize data that projects future impacts and to demonstrate system effectiveness is well beyond where it was a decade ago. And we can expect that to continue improving at an exponential rate.

Glumac’s California energy modelers are using several software applications that take into account future climate projects. Cal-Adapt provides data and visualizations that create a variety of climate change-related scenarios and allows us to provide more insightful and climate-focused design recommendations to clients. We’ve also begun working with Ladybug, a suite of open source tools that use data from the IPCC, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and others to provide projectable climate data to create models that demonstrate everything from the changing effectiveness of renewables to the down-line impact on occupant comfort.

These are some of the tools that have already come online and are presenting a much more clear-eyed view of how climate will impact building design in a variety of geographic areas. The next step is demonstrating to clients the long-term value of the up-front investment. But these advanced modeling tools are helping us paint that picture more clearly.

Looking Forward

Our industry is a major contributor to the carbon problem. But the good news is the opportunity lies within us to create the lasting change necessary to drawdown carbon and deliver a sustainable future. By pushing harder for low-carbon materials, by being active with local and regional governments to advocate for stronger regulation, and by doing the hard work of delivering these solutions in an equitable way, we can get there. And the time to act is now.

To learn more about Glumac’s ongoing commitment to sustainability, check out our latest Corporate Sustainability Report.